For an early childhood and television researcher based in Sheffield, July brings with it the promise of two very different (but equally enticing) children’s conferences.

The Children’s Media Conference (CMC) is a national conference for the children’s media industry, taking place every year in Sheffield. Meanwhile, the University of Sheffield’s Centre for the Study of Childhood and Youth (CSCY), hosts a biennial academic conference in July, also in Sheffield. This year, for the first time, the two were scheduled slap-bang, one on top of the other.

For me, engaging with the media industry is integral to the work I want to do and the kind of academic I would like to be. Quite apart from notions of REF-able impact, useful and engaged academic research should take place as part of an open and bilateral dialogue with industry, practitioners and the wider public. Hopping (Challenge-Anneka style) between two conferences taking place over the same three-day period in the same city might have been a slightly surreal experience, but it also offered a unique insight into the prevalent dialogues and constructions of children’s engagement with the media in two very different fields.

I was really pleased when it was announced that one strand of this year’s CMC theme, ‘Making it Happen’, would be an emphasis on diversity and inclusion. In uncertain times, and facing the prospect of pre- and post- Brexit economic instability, attending to the experiences of the most vulnerable groups in our society has become more important than ever. The topic gave me an opportunity to air my own research on social class differences in children’s media engagement in front of an industry audience. The theme also brought us impressive keynotes from poets Lemn Sissay and UK Children’s Laureate, Chris Riddell, as well as an inspirational session from Jessica Thom of Tourette’s Hero.

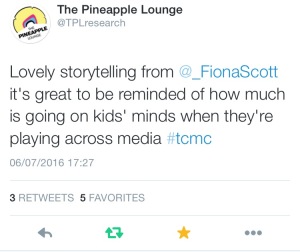

Back in March, when I sent in my research proposal, I had decided to name my own research session ‘The C-Word’ (easy to type, significantly more abrasive to say out loud). In addition to creating an opportunity to tipsily invite delegates to a sniggeringly dodgy sounding research session during Tuesday’s pre-drinks, my title was intended to genuinely provoke. In recent years, the prevalent discourses of (mainly sociological) academic research have made it feel increasingly difficult to talk about (let alone research) class (‘the c-word’). Ulrich Beck famously described social class in terms of ‘zombie categories’, suggesting that this thinking was blinding academic researchers to the real ‘experiences and ambiguities’ of modern life (2014). And yet, as my session highlighted, the UK is currently as inequitable as it has ever been (perhaps even more so). As Diamond & Giddens (2005) point out, the UK ‘suffers from high levels of relative poverty and the poor in Britain are substantially poorer than the worst off in more equal industrialised societies’ (p. 102). As difficult and problematic as models of social classification may be, I believe there is an urgent need to pay attention to social class with respect to all aspects of young children’s lives and experiences. Media texts are often overlooked, but are one of the most important ‘raw ingredients’ that preschool children use to construct their early play and broader interpretations of the world. As such, the nature of children’s engagement with these texts arguably demands as much attention as their engagement with more formal learning contexts. I was heartened to receive very supportive, positive and constructive feedback on my work from the CMC’s friendly delegates.

Academic and commercial research are not always the most natural of bedfellows, but this year, I was delighted to present alongside a number of excellent industry presenters, some of whose insights rang very true in terms of my own research experiences. iGen Insight’s Claire Milner shocked some of the delegates with her data on the significant time parents spend co-viewing television with preschool children. It is heartening to see this phenomenon reflected in commercial research presentations, helping to overturn the very persistent myth that watching television is a solitary activity for preschoolers. Meanwhile, and in contrast to a slight media industry tendency to obsess over the ‘takeover’ of on-demand, Ofcom’s Emily Keaney hammered home the oft-forgotten reality that live TV still dominates for children. She also teased us with the prospect of a new ‘Media Use and Attitudes Report’ dataset, to be launched later this year.

On the other side of town, this year’s CSCY conference explored the social, biological and material dimensions of childhood and children’s everyday lives. My own theoretical framework is much indebted to Alan Prout’s book, ‘The Future of Childhood’, which posits that every ‘device, machine, technology is neither pure nature nor pure culture, but a net-worked set of natural and social associations’ (Prout, 2008, p. 31). I was delighted to have a chance to see Professor Prout speak in the flesh for the first time, as well as presenting my own conceptualisation of children’s media engagement as a social, physical and classed practice.

Though the theoretical framing of the research over at CSCY was noticeably denser, academics and industry researchers alike were asking, and attempting to answer, many of the same questions. In particular, parallels could be drawn between questions of the comparative value and creativity of digital and traditional tools. The University of Sheffield’s Birsu Kandemirci presented some lovely psychological research suggesting that digital and traditional toys were equally stimulating for children’s storytelling. Over at CMC, Maurice Wheeler of The Little Big Partnership explored the creative affordances of digital tools in comparison to their physical counterparts. Both presentations sparked my interest in terms of their implications for children living in less economically advantaged communities. Every child, as Wheeler powerfully articulated, has “all the colours” in his or her digital pencil case.

At the same time, I couldn’t help but reflect on the continued research preoccupation with isolating the role played by ‘digital’ and ‘traditional’ toys into separate variables for clean analysis. Digital and traditional toys are different things, but the role they play in the everyday lives of preschool children cannot be so neatly teased out. Children’s meaning-making at home takes place in a complex web of the biological, the social, the cultural, the spatial, the emotional and the material. In real life, a preschool child will:

- start with a media text in the form of a videogame;

- play it, moving their body and creating verbal dialogue around it;

- search for related content online;

- find and print out a net for a 3D cardboard representation of one of the game’s characters;

- physically cut it out with scissors and paste its parts together;

- co-construct ‘traditional’ physical play with others using the character.

How do we separate for analysis the unique variables in this (real life) vignette? Comparisons between the digital and physical are certainly both interesting and valuable, but we must not forget that they do not reflect the everyday reality of children’s lives.

My thanks go out to all of the individuals who made these wonderful conferences and research sessions happen – amongst others, Greg Childs (CMC), Liam Papworth (Fremantle Media), Miranda Maguire (CiTV), Penny Curtis (CSCY) and Dawn Lessels (CSCY). I am crossing all of my fingers and toes that I will have the opportunity to join you all again the next time around!

July 8, 2016 at 6:46 pm

So cool, and inspiring reading. So true – digital, traditional, online, offline – speaking of children’s play it is all the same 🙂 I would have loved to be there with you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

July 9, 2016 at 2:05 pm

Thank you for your kind words, Helle! Maybe next time you can come along too!

LikeLike